And I Love Them (originally posted on La Loquita del Zig-Zag blog, Wednesday, August 30, 2006):

Light rain is peppering the windowpanes: we collectively managed to dodge Ernesto's bullet. Imagine--just imagine--how things would have turned out if someone else had managed to dodge an assassin's bullets on November 22, 1963.In a nostalgic mood--and nursing a bad cold--I present you with

AND I LOVE THEM

BY GEORGINA MARRERO

Certain things of note in my life sandwiched themselves between the summers of 1963 and 1964. Two of them affected the entire nation… if not the world. Even I – as an eight to nine year old – realized that nothing was ever going to be the same, again.

In July of 1963, we, as Cuban refugiados (or exilados, as we like to refer to life in the U.S. as living in El Exilio) began to aspire to The American Dream. Papi was a third year resident in neurosurgery at Jackson Memorial Hospital. To paraphrase my mother: “His salary – at $219 per month, as well as his age – at 53, were record-setting. He was the oldest resident in JMH’s history.” Given his knowledgeable background, extensive training, and years of experience, he had been appointed Chief Resident.

My sweet natured, shy – yet gregarious, at times – father had befriended many of the staff at the Jackson. A tall, lanky, bow tie clad, pipe-smoking Tennessean had become his special friend. He called my father, “Fred.”

Basil Yates, who figured in our lives for many years to come, came to our financial rescue. Estábamos muy apretados: we didn’t have much money. As my mother used to tell the story: one day, Basil asked Papi how much money he made per month. Papi replied, “two hundred nineteen dollars.” Was it enough to support a family, Basil then asked him. My father, in all honesty, replied, no. Whereupon, Basil reached into his wallet, pulled out two hundred dollars, and handed the money to my – I’m sure –astonished father. He told Fred he’d continue to do this until his friend finished his residency… to which Papi responded, “I’ll pay you back.” Both men kept their ends of the bargain.

So we were able to move from the kindly, shabby tenement, El Vanta Koor (Vanta Court; now Shenandoah Square), to a better apartment building several blocks away. We were still in La Sauguasera, el barrio close to Calle Ocho that was – and continues to be – inhabited by recently arrived immigrants and refugees. Mami and I could still walk to Calle Ocho. Most importantly, I could still walk to Shenandoah Elementary School, where I would begin fourth grade in the fall.

The Amsterdam Palace

Armed with Basil Yates’ generosity, we were able to spend a month at DA BEECH – as Miami Beach’s yearlong residents lovingly refer to their special place in the sun – that July. We rented an apartment in the Amsterdam Palace Hotel (now the Casa Casuarina). We had the middle oceanfront apartment on the second floor.

There was no air-conditioning… but that’s the way Mami wanted it. Las brisas del mar – the ocean breezes – provided plenty of cross-ventilation. Poor Papi was on call thirty-six out of every forty-eight hours, but, at least, he got to sleep in the alcove directly facing the window overlooking the front of the hotel. He rightfully had the best room in the house!

For my part, I played among the statues and fountains on the first floor, ceaselessly rode up and down the elevator, and spent as much time in the ocean as I could. Sometimes I went swimming twice a day. Mami liked to take me in the early mornings, when the sandbanks were built up, and we were able to walk out into the ocean as far as we dared. Also, we were less likely to become sunburned. Oh, really?

My certain thing of note number one was this: I became very tanned that summer. And I remember getting a really bad sunburn: it hurt, and then I peeled for what seemed like forever. However, I kept going back into the water, playing like a porpoise without a care in the world. After all, I was eight going on nine.

DA BEECH held other wonders: The old, decrepit Art Deco hotels; The old folks rocking themselves on the porches of these hotels; The old cafeterias on Washington Avenue, where a little money bought a lot of food; The fifty-cent theaters, often serving up double portions of old – but wonderful – movies. And then there was Wolfie’s.

Already a bit on the chubby side, I could always find room for more. Wolfie’s was a treat: from Tenth Street, we had to trudge up Collins Avenue to Lincoln Road, so I already had an appetite ready and waiting by the time we got there. I remember the pickles, the cole slaw, the rolls, the stuffed cabbage… and the cheesecake. Oh, that cheesecake…

Sunburn. Yes. There’s a picture of me at a party, sitting next to Papi, where I’m muy bronceada y rosada, all at the same time. Very bronzed and rosy, indeed, after all that Nivea, all that peeling: I’m wearing a white shift with big roses on it. For some reason, I’m shyly looking down at my hands. Papi is glancing over at me. And – yes – for some reason, this is the way I remember myself from the summer of 1963.

Late summer found us in the new apartment. For three years, I had all but stumbled out of bed to get to school, as El Vanta Koor is located next to Shenandoah Elementary School. Now I walked to school, either with Mami, or with some of our new neighbors’ children, who had become my new friends.

As my English had improved tremendously, I fully expected to find myself in an English speaking fourth grade classroom. Full of both eagerness and dread, I entered the fully mainstreamed classroom. To my horror, I found myself being directed back to my third grade bilingual classroom! Was I being held back?

It turned out a number of us were in the same predicament. All of us were cubanitos. We had all done well enough in third grade… but, perhaps, not well enough? Our old/new teacher instructed us to sit down at a separate table, and that is where we remained all year. We weren’t being held back: we were being both linguistically and culturally enriched. Shenandoah – along with Coral Way Elementary – had one of the pioneering bilingual, bicultural programs in the nation.

Our teacher was Puerto Rican. She offered us bilingual instruction, but only when – and if – she had to. I had been her third-grade classroom spelling champion the year before, having achieved the honor with the word, “handkerchief.” Slowly, but steadily, my grades had improved over the course of my first three years. No F’s since the six I had received in first grade, when I had spoken absolutely no English. However, I kept receiving my fair share of D’s… in Physical Education.

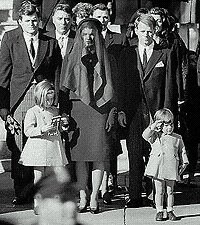

It was around that table that Mrs. Echevarria’s “transitional” fourth graders experienced certain thing of note number two: on Friday, November 22, 1963, at just after two p.m., our principal, Miss Hatfield, made an announcement over the loudspeaker. President Kennedy had been shot and killed. We were instructed to stand up, observe a moment of silence, and then we sang “God Bless America.”

Were we allowed to go home early? I’m not sure. What I do remember is that I – along with my mother and some neighbors – watched the world, as we knew it, change in front of our eyes over the course of the next four days. I remember watching Walter Cronkite – “Uncle Walter,” as I call him to this day – choke up in front of national TV. I have a fleeting memory of the shot fired by Jack Ruby that killed Lee Harvey Oswald. I remember the grimness on LBJ’s face as he took the Oath of Office, with Lady Bird and Jackie flanking him on either side. I remember Jackie draped in black. I remember the solemn procession of the horses at the funeral. And I remember John-John saluting his father.

What I didn’t know at age nine was that several cubanos were considered to be accomplices in the assassination plot. Playa Girón – The Bay of Pigs invasion – had been mapped out at El Vanta Koor. This I knew, even as a child.

Of course, we know by now that we may never really know. This nine-year-old cubanita really knew only one thing: the President of the country that had welcomed us three years earlier was dead. And we felt very sad.

As fourth grade coursed along, though, the course of actual world history slipped into the background. By the end of 1963, my friends and I had begun to listen to four young men from Liverpool, England, blaring forth, “I wanna hold your hand,” in a way that shocked our elders. The Era of The Beatles had begun: this became our certain thing of note number three.

At least one of us muchachitas had the hit single in her hands by some time in January of 1964. I remember that we played it, over and over… and sang along, of course. Loving – nay, being in love with – The Beatles was quite the “girl” thing.

Whom did we love the most? Paul. And John. And George. And Ringo. In that order, because the “cuteness” factor was as – if not more – important to my prepubescent friends and me than their actual degrees of talent. I think some of our friends who were boys actually became quite jealous.

Everyone watched The Ed Sullivan Show in those days. On Saturday, February 7, 1964, The Beatles landed at Idlewild (now JFK) Airport, to mobs of screaming girls. On Monday, February 9, 1964, they made their first appearance on Ed Sullivan. Even before Ed had finished introducing “these youngsters from Liverpool,” the screams had begun, again. Wails, sobs, hand wringing… and tears. I could barely hear The Fabulous Four. I was probably screaming right along with the loudest of them.

Exactly one week later – on Monday, February 16, 1964, The Ed Sullivan Show was aired live from The Napoleon Room at the Deauville Hotel, on Miami Beach. I don’t remember knowing anyone who had tickets. Oh, if only…

At least we had the singles, and, later on, their first album, “Meet The Beatles.” I wish I remembered my mother’s reaction to “these youngsters.” She probably didn’t like them too much. Another of “mis manías” – my obsessive habits - she probably thought.

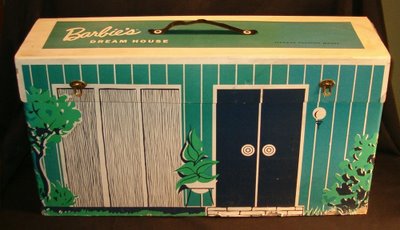

She’d already had her fill of my other one: my Barbie dolls. Though they didn’t have much money, my parents sweetly – and patiently – nurtured this other “girl” craze of mine. I lacked nothing: doll carriers; outfits; the orange sports car; the huge red bed (I’d wanted the pink canopied one, instead); the vanity; and the piano that played “I Love You Truly.”

Sometime between 1963 and 1964, they bought me the ultimate Barbie possession.

Barbie’s Dream House was made out of hard cardboard, with room dividers – and furniture – also made out of cardboard. It folded up, neatly, into an oblong “purse,” of sorts, for easy storage, and it had a handy-dandy black plastic handle. Still large and cumbersome, the house took some effort for even a chubby nine-year-old to lug around. Huffing and puffing, I managed. Proudly. Usually, though, it sat on the floor in the alcove where I used to study, right behind my desk.

And that’s where my certain thing of note number four occurred: right behind my desk. Rocking back and forth in my chair one day, I toppled backward. And squashed my Barbie Dream House almost beyond recognition.

I know I cried.

The summer of 1964 we moved to Milledgeville, Georgia. I was mainstreamed for the rest of my schooling. I remained addicted to The Beatles, and to my Barbie dolls, for several more years. My Papi eventually returned to Miami, and so did Mami and me.

But nothing would ever be the same, again.

Copyright, 2004 by Georgina Marrero 1942 words All Rights Reserved